Home

Engagement

Water Use in Auckland and beyond

Raymond Chang, an environmental scientist with BECA, spoke in a Lenten series on Water about the way we use water in Auckland

Unlearning for creation’s sake

Jesus and the politics of power

Climate Crisis Statement

Media interviews

A day in the life of the Auckland City Mission

Matthew's Leadership

John the Baptiser

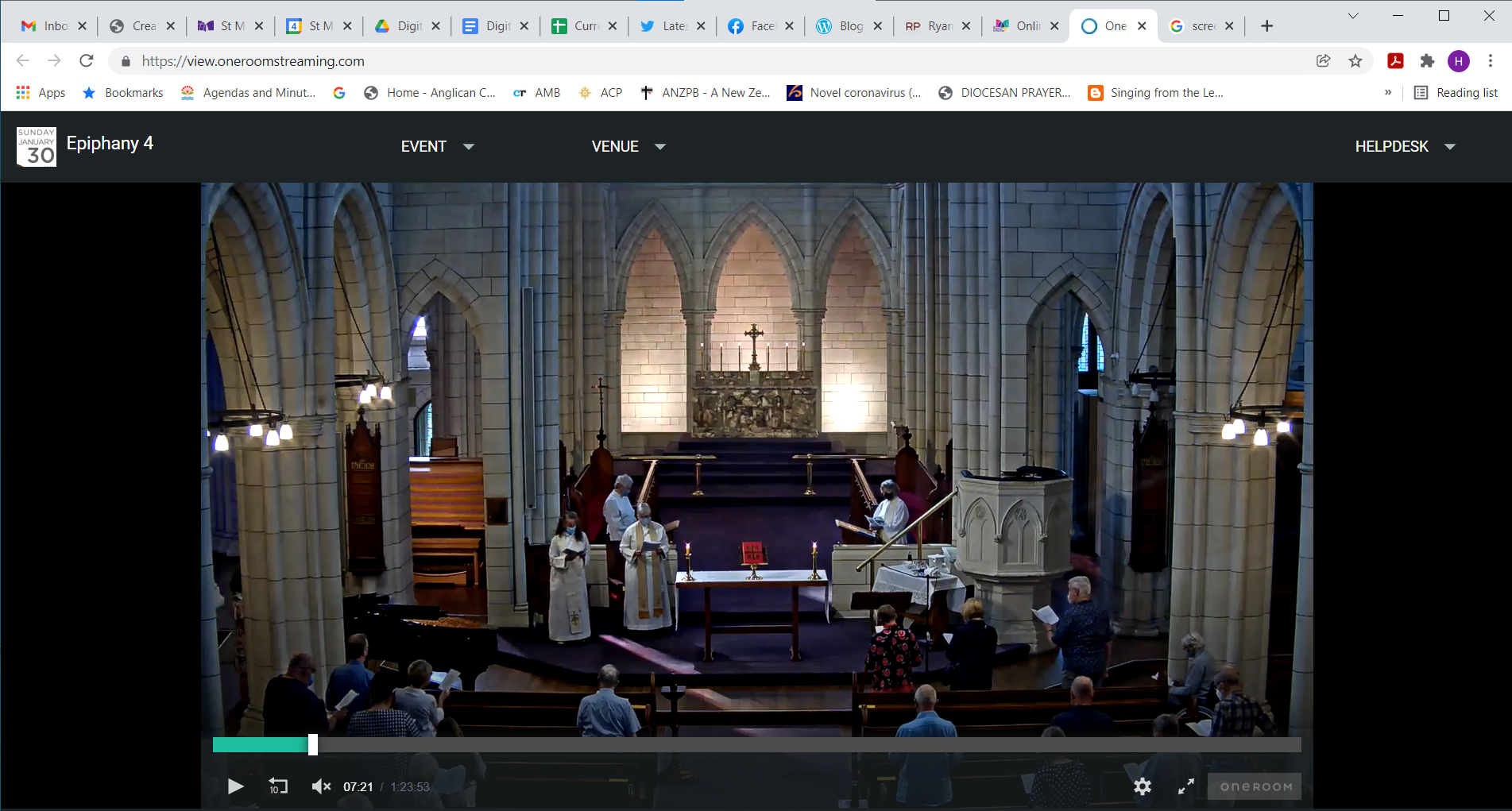

Hybrid worship